The edge of the Little Karoo, an arid semi-desert region northeast of Cape  Town, is where one finds, not far from the small town of Prince Albert, Hell.

Town, is where one finds, not far from the small town of Prince Albert, Hell.

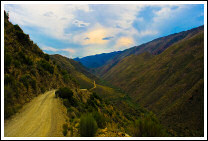

To go to Hell (Hel in Afrikaans), you must drive through a steeply climbing section of the stunning Swartberg mountain pass, some of it quite narrow and unpaved. But that’s nothing. You are still on a road from A to Z.

Somewhere around C or D, however, the civilized dirt road branches off to the right as a laconic sign warns you: Gamkaskloof – "Die Hel" – 50 km – 2 hours.

…

Well  that would’ve been nice. Our intel’ said 2:30 hrs and up. And we knew our many photo stops were probably going to stretch that timing by half. Said intel’ also specified how to negotiate the last portion of the ride: "You get to the top of a steep, infinitely winding dirt road leading down through a series of hairpin bends to the bottom of the valley, 1000 meters below. You stop there and watch the entire length down for incoming traffic that you couldn’t meet head-on on the exposed and narrow road. Even if you see none, still wait 10 minutes just in case. Then you throw yourself in low gear, and may God be with you." Boy, were we glad we had the 4X4 Turbo Landcruiser!

that would’ve been nice. Our intel’ said 2:30 hrs and up. And we knew our many photo stops were probably going to stretch that timing by half. Said intel’ also specified how to negotiate the last portion of the ride: "You get to the top of a steep, infinitely winding dirt road leading down through a series of hairpin bends to the bottom of the valley, 1000 meters below. You stop there and watch the entire length down for incoming traffic that you couldn’t meet head-on on the exposed and narrow road. Even if you see none, still wait 10 minutes just in case. Then you throw yourself in low gear, and may God be with you." Boy, were we glad we had the 4X4 Turbo Landcruiser!

Die Hel, as one story goes, was not so called by its inhabitants – the isolated valley actually being a strangely lush and hospitable oasis thanks to the Gamka river that runs through it – but by the British tax collectors or stock inspectors who had to endure the voyage there and back.

Only access path to Hell, the 50 km long dirt road wanders endlessly  between two high ridges and you find yourself wondering if you’ll ever get there, and if, when you do, it will still be there.

between two high ridges and you find yourself wondering if you’ll ever get there, and if, when you do, it will still be there.

The valley of Hell itself, the Kloof, is 10 km long and narrow. After that, the road ends. There is nothing beyond. You must turn around or stay forever.

The first part of the trip was, as we would later agree, by far the most spectacular. There had been a bush fire in a not so distant past and tall charcoal-black flowers stood at eye level as far as those could see, silent guardians of a pointless secret, lifeless skeletons erected above a ground already re-fertilized and moving forward busily.

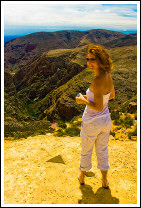

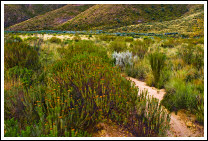

Then  we discovered that enough water actually flowed down from the barren slopes above us into the flat plateau where our road cruised right and left, enticing an amazing vegetal cocktail to establish permanent residency. Marie was in pure botanical heaven, hell to come or not. Even I, from the height of my almost complete ignorance in the field, was fascinated.

we discovered that enough water actually flowed down from the barren slopes above us into the flat plateau where our road cruised right and left, enticing an amazing vegetal cocktail to establish permanent residency. Marie was in pure botanical heaven, hell to come or not. Even I, from the height of my almost complete ignorance in the field, was fascinated.

Many pictures were taken, even more stops requested, and exclamation points left hanging in mid-air. Then the landscape got drier – and stretched to infinity. The path was bad, our maximum driving speed hovered around 25 km/h and too often, rocks and potholes had to be negotiated with an almost complete stop.

When we got to the top of the last challenge we looked down at the road for incoming  enemy troops, saw nothing, considered waiting the recommended 10 minutes, didn’t, and dove in. Nobody came shooting up from a blind corner during the descent. Maybe they saw us come down and waited.

enemy troops, saw nothing, considered waiting the recommended 10 minutes, didn’t, and dove in. Nobody came shooting up from a blind corner during the descent. Maybe they saw us come down and waited.

The drive through the long valley took forever. At first pretty and extremely green under its cover of lush trees, it soon got boring and incredibly rough. In places we could have sworn we were driving on a dry river bed, which in time became true because there had indeed been a flood. But we pushed on, lured by the promise of a wealth of historical information in some public house at the end of the road.

The house  was closed. Next to it, a generator huffed and puffed loudly right where we would have had our picnic. Vanquished, we bailed and crossed the entire valley again to go eat by the entrance near a baboon-proof garbage can.

was closed. Next to it, a generator huffed and puffed loudly right where we would have had our picnic. Vanquished, we bailed and crossed the entire valley again to go eat by the entrance near a baboon-proof garbage can.

A few of the old houses remain in Die Hel; they have been renovated and are rented out as self-catering units to the braves who venture this far into nothingness and bring enough supplies along to survive a week. The houses still carry the family name of their last owner. It took me a while to understand: all of them, 10 or so, belonged to a Marais. They must have married each other for generations, without ever leaving the safety of the valley. Their gene pool would have been as dry as the moon. To  this day, it is remembered that the locals were a little… strange.

this day, it is remembered that the locals were a little… strange.

On the way back, a beautiful distant storm slowly grew into a mighty giant in the north and inched its way towards us, finally reaching the road as we hurried down the final pass into Prince Albert. We had been to Hell and back; 120 km of dirt road in seven hours. That night, the wine tasted heavenly.

Comments

Marie