We awoke to the chirping of birds everywhere. Our tree didn’t host a nest but the sociable weavers lived nearby and they flocked in for an early visit, cunningly sensing that a breakfast was about to happen.

These weavers are quite remarkably friendly birds (see previous post for picture). They inhabit huge colonies patiently built in camel thorn trees and divided to form individual nests, more or less oriented downwards. It would seem that there is a central chamber but I didn’t push my investigation too deep. I’ve read  somewhere that in such harsh and hostile climate they normally manage to get all the water they need from an insect diet, so the water we served them must have tasted extra sweet. We soon found out we could attract nearly the entire flock with rusk crumbs (the bloody things are nearly indestructible and not good for anything else anyway) and our campsite was besieged by so many birds that we almost lost control. They were, however, extremely polite, unafraid and delicate, a rare combination that meant no risk for our fingers but did threaten the table. Packing up took a little longer than we had planned. When we left the campsite, the endearing overfed weavers must have gone for a collective nap.

somewhere that in such harsh and hostile climate they normally manage to get all the water they need from an insect diet, so the water we served them must have tasted extra sweet. We soon found out we could attract nearly the entire flock with rusk crumbs (the bloody things are nearly indestructible and not good for anything else anyway) and our campsite was besieged by so many birds that we almost lost control. They were, however, extremely polite, unafraid and delicate, a rare combination that meant no risk for our fingers but did threaten the table. Packing up took a little longer than we had planned. When we left the campsite, the endearing overfed weavers must have gone for a collective nap.

The next dirt road, which according to our well-folded but probably flawed map should have lead north from Aus, was hard to find. When we finally spotted it, further down than expected on the main B4 and very much unannounced, we were left to ponder the consequences of wandering onto a road that, obviously, nobody wanted to be on.  But as we eased our way northwards down an immense stretch of perfectly straight road, lifting a huge cloud of white dust that followed us like a trail its comet, the landscape turned yellow and wide, and we were drawn into it as if bound by a spell, without any more thoughts nor hopes of turning around.

But as we eased our way northwards down an immense stretch of perfectly straight road, lifting a huge cloud of white dust that followed us like a trail its comet, the landscape turned yellow and wide, and we were drawn into it as if bound by a spell, without any more thoughts nor hopes of turning around.

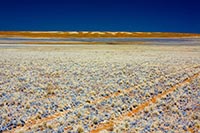

There isn’t much I could say about the drive to Sesriem without the support of photographs. We had entered a singular space made of a million perfect images but missing its vertical dimension. This world had lost its height and now laid flat and thinly layered all the way to the horizon. The landscape was being crushed by an endless sky of the deepest blue, perfect and immaculate, deliverer of an invisible but tenacious heat that only blossomed as it coated the ground in tones of gold and reds and whites, and then oozed back up in mesmerizing mirages.

On our right, for most of the way, unfolded a very low outcropping of rocks, marking the actual edge of the desert and beginning of the subsequent inland plateau. Left, as far as the eye could see, stretched a field of very low and dry grass of yellows and steel blues over a reddish soil. An endless fence formed a rather theoretical boundary and defied the imagination, extending so far that its perspective morphed into a solid shrinking triangle.

Eventually we turned west on the D707 that loops far into the desert’s edges, getting closer to the first real dunes of the trip which we only identified as such at the last minute because of their eerie orange color. It was the most amazing part of the day’s leg. We lost precious time on countless photo stops.  I think we were a little speechless and spaced out.

I think we were a little speechless and spaced out.

Around five o’clock, after a full day of wonders and fierce heat, we reached Sesriem, unique gate to Sossusvlei. We had arrived at our destination. Beyond that point, we hadn’t bothered planning much, leaving the rest of the trip to improvisation and allowing for the unexpected.

We checked into the official, government-operated campground, despite the failure of our very necessary advance booking – read here “because of the completely worthless services of a local agency we had stumbled upon on the web.” Thanks to Marie‘s charm, though, we scored the best campsite towards the end of the compound, with nothing between us and the distant sand dunes. The contrast between the privately owned Aus campground and this official machine was striking, but in the end, our goal mattered more than the means and we were delighted to stop for a few days. We settled into our third night, pitching the tent underneath a gigantic camel thorn inhabited by a comical lizard that came out every time we turned the tap on. Yes, the site had running water. This was no third-class third-world country and someone understood the importance of adventure tourism as a gold mine.

As the afternoon faded into a beautiful evening and the wind picked up and hauled like every night, barking geckos began their symphony all  around us and we knew we had arrived. This was somewhere strange, different, a place that pushed our comfort zone sideways, a little corner of sand under a big tree next to the oldest desert on Earth. Sure there were people nearby. Our world has become so friendly to travelers that it’s increasingly difficult to avoid sharing its beauty with our peers. But this was no crowd, and the few other visitors were diluted into such immensity that they became quite tolerable.

around us and we knew we had arrived. This was somewhere strange, different, a place that pushed our comfort zone sideways, a little corner of sand under a big tree next to the oldest desert on Earth. Sure there were people nearby. Our world has become so friendly to travelers that it’s increasingly difficult to avoid sharing its beauty with our peers. But this was no crowd, and the few other visitors were diluted into such immensity that they became quite tolerable.

Darkness and its best friend solitude closed in on us, the braai was lit up, our headlamps came into action and we ate with ferocious appetite. A jackal materialized in the faint glow of our candles but disappeared as soon as we acknowledged its presence. The ablutions block again had hot showers, a luxury I could never resist and was incredibly happy to find in the legendary middle of nowhere. Our mattress inflated, we carefully zipped up the tent to keep mythical jumping spiders and very real scorpions out and listened to the geckos. Later, when all was pitch black and the wind had calmed down, the jackal visited again. It would be back every night, shy but determined. In the morning, Marie found its footprints all around the tent. It would seem our jackal liked camping too.

«Roasted in the Namib» Series

Want to read the entire series of stories? Start here

Already reading sequentially?

Previous story: Roasted in the Namib, Part 2 – Namibia begins in Aus

Next story: Roasted in the Namib, Part 4 – Sossusvlei, or taking the pulse of the oldest desert on Earth

Marie’s recount: Namibia

Comments

Marie

dinahmow

Vince

Vince

Lambert