Like most storytellers, I enjoy the occasional temporal digression. It keeps me (and hopefully you too) sharp and focused. So let’s rewind a  bit. The last post recalled the end of our stay at the Golden Gate National Park and was leading up to a second incursion into Lesotho, a full crossing this time, to culminate both metaphorically and geographically with the infamous Sani Pass ascent. That story will come soon. But we had already ventured into the Mountain Kingdom between our two stays at Golden Gate and this, should you choose to read on, is the report of such excursion.

bit. The last post recalled the end of our stay at the Golden Gate National Park and was leading up to a second incursion into Lesotho, a full crossing this time, to culminate both metaphorically and geographically with the infamous Sani Pass ascent. That story will come soon. But we had already ventured into the Mountain Kingdom between our two stays at Golden Gate and this, should you choose to read on, is the report of such excursion.

We left the National Park with an open red wine bottle in the fridge along with a couple of beers. We were willing to part with these, should the border crossing officials prove to be as thorough as we had been warned they could be.

A short drive took us back along R711 and R26 to the vicinity of Fouriesburg where we turned sharply left and headed for the Caledonspoort border post, entering the small country from the northwest. This was an out-of-the-way crossing; one that, we hoped, wouldn’t delay us much.

The first stop was the South African control post. It had consisted of a triple-authority checkpoint at last year’s major crossing into Namibia: Customs, Immigration and Police. Out here, a rural location where many seemed to cross on foot  and most were possibly unable to sign – let alone read – a form, all formalities were expedited at a single window. We parked the Landcruiser, walked over to a shaded booth, showed our passports, offered the Vehicle Owner Authorization letter that we had lacked the previous year – it was politely disregarded as a nuisance – and were waved through.

and most were possibly unable to sign – let alone read – a form, all formalities were expedited at a single window. We parked the Landcruiser, walked over to a shaded booth, showed our passports, offered the Vehicle Owner Authorization letter that we had lacked the previous year – it was politely disregarded as a nuisance – and were waved through.

A few hundred feet down the road, similar in its modest attributes and size, was the Basotho control. We parked again, noticing that we’d have to pay an entry fee of R40 and presented ourselves at the booth, where we were handed a couple of forms to be filled. Forms were expedited and handed in. A loud stamp echoed twice as our passports were approved and we were sent on our way. At the gate, which remained closed as we drove in, a friendly female officer explained that time had come to pay the fee. The gate opened. We were in Lesotho.

Marie and I looked at each other. It had been an anti-climactic border crossing; we wondered what all the fuss had been about and had to agree we had wasted a lot of good wine for no reason.

The Mountain Kingdom of Lesotho is worth a few words of introduction. Completely landlocked within South Africa, the 30,000-km2 country is roughly the size of Belgium, or of the U.S. State of Maryland. Its lowest point is located at 1,400 meters  above sea level and eighty percent of the country sits above 1,800 meters, inducing the possibility of snowfall all year-round on the highest peaks that culminate above 3,000 m.

above sea level and eighty percent of the country sits above 1,800 meters, inducing the possibility of snowfall all year-round on the highest peaks that culminate above 3,000 m.

Lesotho’s two most significant and diametrically opposed resources are diamonds and water, the latter being mostly sold to South Africa. The country is plagued with typical third-world calamities such as a high occurrence of child labor and an HIV rate among the highest worldwide. Surprisingly, its literacy rate is one of the strongest in Africa, even though seventy five percent of the population is rural. But forty percent of these two million people live below the international poverty line of US $1.25 a day – Wikipedia dixit.

From the border, we headed towards the nearby town of Butha-Buthe, watching our speed as the book mentioned a country-wide limit of fifty km/h with the exception of rare “freeways” where the limit was bumped up to eighty km/h. There was no way of telling whether or not we were driving on such freeway, the road being ordinarily narrow and unmarked, and we took no chances. Local drivers and taxis were passing us at high velocity but such is the fate of innocent travelers in mysterious foreign lands: you err on the side of caution until you get baptized with fire and then decide to either never return or become a fire-walker yourself.

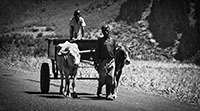

Immediately, Lesotho was different. Subtle differences for the most part but that blended together to paint a shifting reality. We had entered a small new world. People were very short. The kids that played everywhere were so tiny it was hard to figure their age. That could have been a result of malnutrition, or not. These folks walked a lot. Very few cars were used, and most of those were farm pick-ups, not private vehicles. Short donkeys were the local transportation icon. Basotho adults looked proud, or maybe unfriendly, or even just distant. Very few smiled or waved back, but most stared with an inscrutable gaze.

The kids were a different story. They sometimes stared, sometimes shouted, and at times smiled and cheered. The outcome seemed random. We obviously stood out like a sore thumb, in our Luxurious Landcruiser packed to the roof with supplies. The kids who waved at us did so with gestures we didn’t understand. They could have been asking for money. As a matter of fact, they probably were. This was the twenty-first century. News of the First World’s riches had reached even the most remote of places, and the word was out that the inhabitants of said World liked to travel and display their wealth. And occasionally, distribute it.

Butha-Buthe was bustling with activity. Lots of street vendors, lots of improvised stores, lots of shacks and containers. I have always been amazed and fascinated by mankind’s visceral need to acquire goods, whether from the top of empires or the bottom of abysmal poverty levels. Lesotho is said to be one of the poorest countries in Africa. Yet everyone, it seemed, was out buying and selling. A hat. A fruit. Fly-covered meat. Cheap DVD’s. Water. Phone time. Hope.

We left the small town behind us and turned onto a freshly paved road that lead to the newly opened Tsehlanyane National Park. There were so many obstructions on the road, people, kids, donkeys, dogs, sheep and horses that the speed limit was actually out of reach. The younger woman wore modern dresses and held colorful sun umbrellas. Older woman, their clothes more typical of the fields, carried huge loads of wood the traditional way, on their head, a terrible chore that had us ponder the condition of their necks and vertebrae.

Men herded sheep, mounted on Basotho ponies – a local breed of short horses – with the help of dogs. They wore heavy blankets despite the heat. Kids were coming back from school and we had to keep our eyes on the road in fear of an accident. The accident might not have been what one would expect. We had heard stories of stones being thrown at cars and  were a little nervous, our football project postponed.

were a little nervous, our football project postponed.

Because you see, behind us underneath some cover, were two cheap footballs. Back in Cape Town, Marie had decided to buy them on the spur of the moment, with our Lesotho trip in mind. The FIFA World Cup was coming to South Africa that summer and football was a hotter game than ever. She figured that rather than handing out monies, thus teaching the kids to beg, we might as well bear real gifts. Once on Basotho roads, however, and after being exposed to the local indecipherable attitude, we suddenly felt reluctant to go through with our plan. We had become poverty-shy.

Eventually, we reached the National Park. We were granted access after registering at the gate as guests of the Maliba Lodge, a high-end resort located entirely within the park but privately operated. We’d booked a self-catering unit for more money than we should have, enticed by the remoteness of the premises and rumors of a locally run botanical garden, highest of its kind and irresistible lure to Marie’s deeply rooted floral instincts.

Everything at the Lodge looked and smelled like new. The resort had only been up and running for weeks, maybe months. The managers who greeted and registered us in were not yet too particularly knowledgeable about the area. I think they were focusing on newly-built and not-properly-tested-yet kinds of issues – water leaks, peeling paint and plumbing surprises, I suppose. The botanical garden was disappointing. We never saw another guest. The huge resort appeared to have been running at idle.

We got our key and drove down a very steep road to our cottage, a gigantic two-story  house lined up with three other identical units by a beautiful mountain stream. The place had four bedrooms, could sleep up to ten people and featured three toilets plus a bathroom with a full bath and twin shower stalls upstairs, something I had never seen anywhere in the world but that makes so much sense.

house lined up with three other identical units by a beautiful mountain stream. The place had four bedrooms, could sleep up to ten people and featured three toilets plus a bathroom with a full bath and twin shower stalls upstairs, something I had never seen anywhere in the world but that makes so much sense.

It took me five minutes to back the Landcruiser up into a minuscule parking space at the front of the cottage. They’d built a mansion able to host a large family but hadn’t given much thought to the vehicle that was likely to carry such a group. We offloaded our supplies and prepared a snack. The stream that flowed clear and fast just outside the back door was so loud we had to speak up when sitting on the porch. But it was pristine mountain water and for someone who suffers from TBSAWD (Typically Brown South African Water Disdain)* like me, it looked heavenly.

After having lunch on the porch, we set out for a walk across the river and along the opposite bank, in search of endemic flowers and all things new. We found a beautiful pool in the stream and I couldn’t resist a splash. The water was quite chilly but still warmer than Lynn Creek had been back in Vancouver. We then walked further up into a valley, finding many incredible flowers and a few porcupine quills. When we hit a locked gate, we turned around. The park was protecting its content: us. We were back for sunset. Dinner was cooked on the BBQ, or braaied, and savored at candlelight while the sky turned dark and stars appeared one after another.

We slept like babies. The following day, we relaxed and bathed in the chilly stream water that sparkled in the sun. Later,  we hit the road again and drove the way we came, out of Lesotho and back to Golden Gate. We would spend more time there and later cross once more into Lesotho to go tackle the Sani Pass, all the way to the east into the Drakensberg mountain range.

we hit the road again and drove the way we came, out of Lesotho and back to Golden Gate. We would spend more time there and later cross once more into Lesotho to go tackle the Sani Pass, all the way to the east into the Drakensberg mountain range.

Little known to us, our differential lock was finally going to be put to the test. Through the repeated assaults of Mother Nature, in-cloud zero visibility, landslide-grade torrential rains, and with the steepest, rockiest, most unnerving dirt roads we’d ever seen, the Drakensberg was going to challenge us. It had, after all, a reputation to uphold. But so did we.

* South African fresh water isn’t necessarily dirty, though. Its brown coloration is due to a pigment in the fynbos that covers most of the land. Sigh.

«Cartwheels Over Lesotho» Series

Want to read the entire series of stories? Start here

Already reading sequentially?

Previous story: Cartwheels over Lesotho, Part 3 – The Ladybrand Disappointment

Next story: Cartwheels over Lesotho, Part 5 – Differential Lock on the Sani Pass

Marie’s recount: Lesotho

Comments

Marie

Val Palk

Sigrid

Jay

Vince

frank@nycgarden

Vince

Emannuel