I have long known – and dreaded – the unavoidable fact that after three-and-a-half years of running along Vancouver’s Seawall, Montreal and the Big Apple would pose some serious challenges to my exercising routine. If there is such a thing as a runner’s high, I knew I was headed for my runner’s low.

With a difficult month-long campaign in mind, I’ve began to investigate New York as a running ground, looking for exclusive pedestrian paths, parks and other ideal areas. An initial search confirmed what I had feared; Vancouver, Stanley Park and the Seawall could never be matched. Starting a run in Brooklyn was going to force me to run in the street, something I haven’t done in almost four years. And it was going to make me aim, via various routes, towards either Prospect Park or Manhattan’s waterfront.

Google Maps and especially the Gmaps Pedometer are fantastic tools for calculating distance and establishing routes, but they only serve for approximate planning or retrospective analysis. With so much to explore, so many experiments to be run – pardon the pun – and so many variables involved, the prospect of my runs became a little dark. I don’t use running as an exploration game where diversity and surprises take the lead. I need to have a few well designed routes and stick to them until they become hypnotically rhythmic and I know exactly where to pace and where to push. The view is there as a reward, not a distraction.

So I indulged in a new toy, giving myself a few weeks to get acquainted with its multiple functions. I bought a refurbished Garmin Forerunner 305. The little beauty is barely larger than a watch on my wrist and arrives with a chest-worn heart rate monitor sensor, which will come in handy because I want to start High Intensity Interval Training. But most of all, it is GPS equipped and plots distance and speed in real time. Wow.

Suddenly, I could improvise, turn right and left, be stopped by a traffic light, change my mind, double back, and the 305 kept track of it all, live. My running most likely has changed forever. The Forerunner is a brilliant tool and while wearing it won’t make me a better runner, trusting it might.

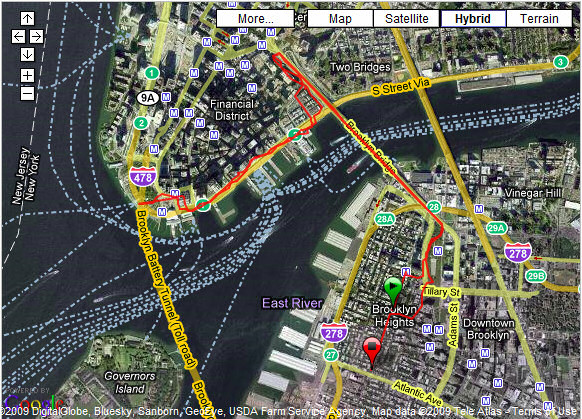

I set out for my first Brooklyn run on July 16, having spent 12 hours on the train from Montreal the previous day. New York was experiencing its first real heat of the summer and humidity was soaring. I opted for running across the Brooklyn Bridge, down to the tip of Manhattan and back, which was supposed to yield just about my usual 10 km.

The Forerunner looked at me funny on a street corner when I had it acquire its satellites; it had become used to Northwestern Pacific skies. I must have looked funny too. I was sweating even before kicking into a slow warm up jog. I’d bought a small water bottle but seriously wished I had my Camelback.

From Henry Street, I aimed right towards Walt Whitman Park because its path would be familiar ground and it leads straight unto the bridge via a dark staircase. I started slowly, with the firm intention of finishing as slowly, acclimating to the heat and the crowds. I had no idea.

From a pedestrian perspective, the Brooklyn Bridge is a zoo. There’s no other way to put it. It features a superb reserved path located above the car lanes on the south side of the structure and divided in two by a white line. Pedestrians on one side, bikers on the other. At least, that’s the theory. It turns out, however, that the bridge is busy 24 hours a day and plagued by an unusually high concentration of tourists, to whom the white line means about as much as the CDI of an old analog VOR Indicator. What, you have no idea what I’m talking about? My point, exactly.

Trying to run through that traffic was like flying IFR in a sky filled with crazy VFR pilots, out of control, off course, chasing their needle, oblivious to other traffic. They step up suddenly in front of you and your only option is to jump into the bike lane and hope to avoid a collision.

By definition, a bridge features two inclines, one going up and the other, down. By the time I had verified the first fact of that statement, I was already sweating profusely, quite exhausted, and my heart beat was an alarming 10 BPM higher than usual. And I hadn’t even done one fifth of the intended 10K. I tried to use the descent to recover and cool off, but as I approached Manhattan, a new fact became alarmingly clear: there would be no cooling off, and my heart was stuck on high.

The slight breeze that had blessed the bridge disappeared and was replaced by heavy exhaust. By coming down the bridge, I had reached the peak of civilization. With a deeply disturbed thought about Stanley Park’s incredibly pure air, I contemplated passing out to benefit from an ambulance’s O2 supply but rejected the idea since they would probably have charged me half the cost of the ambulance for it.

So I pushed on, doubled back towards the water, passed under a highway and joined the waterfront, zigzagging to negotiate with more tourists. The old adage spun in circles in my head: "If it’s tourist season, how come I can’t shoot them?" From there, it should have been relatively smooth sailing to my turnaround point, somewhere near Battery Park. But this was New York and as I was learning fast, plans here must be very flexible.

A little beyond an old sailing vessel docked near the highest tourist concentration, my waterfront path was blocked by barriers and a heavy police presence. I had to divert to the street. Over my left shoulder, I saw 3 large helicopters on a landing pad, and recognized the famous United States of America lettering. I couldn’t believe it. I wouldn’t be allowed to run my waterfront route because the President was in town. New York is full of restrictions. It’s hard being a citizen here, I would imagine. One must allow for presidential movements.

By the time I reached Battery Park, I was totally beat up. The stop-and-go style of street running had taken a heavy toll on my rhythm and even as the late afternoon turned into a hazy evening, the heat was still tremendous. I barely looked at Lady Liberty stranded on her island, and did a 180 back. Down here, at the very tip of Manhattan, the crowd was much more local, lots of suits and high heels, but nevertheless quite annoying.

I dragged myself and my forerunner back to the bottom of the Brooklyn Bridge, ignoring until the last minute the terrible fact that I would have to run back uphill before I could slide down towards Brooklyn and my salvation. Surprisingly, I made it to the top of the bridge without hitting anybody. It must have been the snail pace I had fallen into.

Down on my side of town, I followed the little park back for a while, turned right and then left, and I was done, and Marie greeted me with the sweetest smile, and the cat purred and lead me to his food bowl, hopeful. I was home for now.

I looked at my wrist: I had fallen short of the intended 10K and gone for 9.5. That would have to do. The good news was that the worse was over. There would be a lot of psychological trauma to come which I was hoping to survive without therapy, but physically, the next run would be easier. I had crossed an invisible line. I had drawn first blood.